Alps Divide 2024 – WINNER

An agreement with the rim, or another milestone in the history of bikepacking.

You are currently reading excerpts from my unfinished book about the Alps Divide. And as the title suggests, I was honored to have the opportunity to close an extraordinary agreement. And what kind of agreement? Read on to find out.

The first edition of the Alps Divide started in Menton on August 7, 2024. This French city, nestled between the Mediterranean Sea, Monaco, and the Italian border, was the gateway to a 1,050-kilometer route with an elevation gain of an astonishing 32,000 meters. The route winds along the French-Italian-Swiss borders and ends in Thonon-les-Bains, France, by Lake Geneva. The event’s rules mirror classic bikepacking rules: each participant must complete the designated route under their own power, using GPS, without any targeted support. Along the way, they can only use publicly available services, such as shops or gas stations.

Participants had to deal with many challenges during this race: adverse weather, bike repairs, navigation, replenishing food and ensuring adequate hydration, sleeping in the wilderness, as well as physical and mental hurdles, such as sleep deprivation, muscle pain, and extreme exhaustion…

We weren’t agile snakes, but snails

The route surprised all of us – but not with the picturesque views we had originally imagined. Instead of panoramic mountain peaks, where we’d weave like snakes, we faced endless adversity – ugly, hostile weather that didn’t hesitate to show us its harshest side. My hands stiffen in the constant dampness, my body complains about the lack of clothing. We’re not nimble snakes, but soaked snails, each carrying our burden. Only a few, like me, left their shells at home, because a sleeping bag and a bivvy sack would have meant additional weight that I definitely didn’t need in the hills!

Yet a small part of my heart enjoys the discomfort – the race is turning into a duel of morale and pain, and that means a game with rules I know well.

The second night without sleep brought the first critical situation

As I neared one of the three places where I hit my metaphorical bottom, my night problem began. It was the second night and I hadn’t slept yet. Col de la Bonette, a pass in the French Alps, with its 2,800 meters is one of the highest road points in the Alps, and it has even hosted the Tour de France several times. I climbed up a gravel slope and finally hit the asphalt road that lazily wound around the summit. It was here that the storm caught up with me.

The wind and rain enjoyed their wild dance, as if they were having a love affair with anyone who came their way.

Frozen to the bone, I hid behind a pair of armored doors carved into the rock – a relic from the times when the Maginot Line held out against enemies. No warm drink, no extra layers of clothing, just a down jacket I couldn’t even put on because outside, with the wind, large sheets of rain were falling from the sky. So, I started wildly spinning my arms to get my blood flowing. When I felt I had enough strength to shift gears and brake, I set off again.

The wind occasionally blew into my back, only to suddenly strike me and slam me into a harsh press. I circled the summit from another angle, and suddenly, the column of rain and wind literally knocked my bike from under my feet. I jumped off, and the loaded bike rose into the air like a paper kite. I held onto it with my hand, but who was holding onto me?

Just as I was about to involuntarily take off, everything stopped as if shot. I walked, leaning on my bike. Then I got on and started pedaling. The next sudden and sharp gusts played with me like a paper boat on a wild river. I expected another treacherous strike, which was supposed to come from the right, as there was a shaft just next to the road, deep into the night, and to the left, the wall rose, where I should have been sheltered from the wind. But it came from the other side, from above the summit of the hill. It knocked me to the ground, and the rear wheel landed rim-first on a stone. But I didn’t notice anything, and only today I think that it might have been the first problem in the subsequent chain of events.

The third day started nice, but…

The next day, after a few hours, I treated myself to a rare moment of sunshine and wonderful views of the Queyras National Park landscape. But just a few more hours of night, and I was facing a tough climb to the lake and glacier Sommeiller, the highest point of the Alps Divide race at 3,000 meters above sea level. For climbers or high-altitude hikers, this elevation in temperatures around 0°C and in the rain is no special feat, but for a bikepacker on a long route, it presents a completely different challenge. The rain didn’t stop, and I, who the organizers and racers started calling “Wolfman,” was racing to the summit with Benjamin Maibach. It was during these moments, on the tough climb, that I felt more like a scrawny flea clinging to the tail of a wolf named Benjamin.

The path winding upwards was cutting into the steep slope – zig, zag, zig, zag… And right in one of these turns was a small flat spot where the rock broke, and through its edge, the wind howled, taking more degrees from an already low temperature, which, according to my speedometer, was nearing zero. I chose the worst terrain, timing, and weather for a break, but there was no other choice! That night I took two short micro-naps, as I had trained during Slovakia Divide, and from the third rest, it turned into a long sleep lasting ninety minutes. In a zen-like surrender, I endured this time, wrapped in thermal foil that had been sealed into a sack shape. I didn’t set an alarm because my internal clock always works perfectly – it wakes me up a minute before the set time. It wasn’t deep sleep, more like meditation with crossed arms on my chest, in wet cycling clothes and a damp down jacket. I tried to squeeze enough warmth out of my body to steam myself up, but not too much, because every watt of energy would later be missing.

Other worlds and detachment from the body

In that rest, I once again visited one of my worlds – a black planet, over which I fly. Luminescent flashes occasionally illuminate it with a poisonous yellow-green light. I can only guess how the outlines of horrific shapes of rocks, mountains, craters, and abysses look. During my flights over this landscape, I’m overwhelmed with a sacred awe mixed with terror and some sort of warning. This world, which I occasionally get the chance to visit, paradoxically soothes me with its horror. Perhaps I seek in it what attracts me in this world, which I share with you, my dear reader. Waking up, quickly packing up, and moving my stiff muscles is always the hardest part. My body is cold, the thermal foil is soaked with sweat, and when I get out, even greater cold awaits. My knees are swollen, my legs and arms are stiff, and my calves are like stones. Blocked back is still the lesser evil compared to what I’m doing with my muscles, which have just started regenerating – but I interrupted their regeneration plans, as full recovery would require much more time.

I set off again up the hill, and after a few meters, I heard a strange sound, like a plucking of a high string. A memory of the world with luminescent flashes, where I had just been floating, flew through my head. I didn’t pay much attention to the sound until the next night when I realized, through reverse logic, what had actually happened. And we’ll get to that resolution soon.

On the way, I met Benjamin, who was riding back from the highest point of the Alps Divide because in this section of the race, the route returns along the same path for several kilometers. The climb to the lake is tough, and often I go “walking bus” – as we, middle-aged bikepackers, call walking while pushing the bike beside us. With my bike, it’s not possible any other way. I deliberately didn’t choose a bike with any suspension (shock absorber, suspended fork, suspended stem, or seat post) because of the overall weight of the setup. I knew that in technical sections uphill, it would be a big handicap, but I also hoped there wouldn’t be too many such sections.

And then I realized something I’ve known for a long time. Despite all the advanced technologies that come and go, one unshakable rule remains (not only in bikepacking): no gear, not even the most perfect bike in the world, will ever replace the power of the human factor. It is our experience, preparation, training, and above all, our mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional resilience that determines whether we will make it to the finish line. Our gear can support us, but only we can make the real journey.

Somehow, the tech is failing

The summit sign for the mandatory selfie had fallen, so I took a photo next to it and stuck my WOLF-MAN stickers on the elevation sign. The thermometer showed a temperature below freezing, rain alternated with sharp winds, and thin layers of ice covered the rocks. The AXS electronic shifting stopped working. I changed the battery, but the system still wouldn’t catch on. I just smiled silently through my chattering teeth – I didn’t even have the energy to swear. It seems that the shifting got unpaired, but I couldn’t pair it with my phone because there was no signal. I couldn’t remember how to pair the AXS without a phone! This was really a bad situation. I was wasting precious time, the wind was blowing, and I felt exposed. Then I realized that the Blips on the shifting worked. Blips are small buttons at the end of the handlebars that can also shift gears. How is it that the Blips are working when the main shifting isn’t? The Blips wirelessly connect with the main shifting, which then sends the signal to the derailleur. Finally, I realized the cause of the problem – the main shifting’s battery had died, but not completely, so it could still transmit the signal from the Blips to the derailleur. So all I had to do was replace the button battery in the main shifting! I’m an experienced bikepacking wolf, so of course I had a spare. But my hands, marked by years of effort and now frozen, weren’t working for fine motor skills in the cold! Plus, the battery was hidden under the brake lever, which was wrapped in tape. What would normally be a five-minute task took much longer in that cold, at the most annoying spot of the entire Alps Divide. And that wasn’t all. While inflating the rear wheel, I realized that the high-pitched sound was a broken spoke. Of course, it broke quite unfortunately, right at the end of the nipple, which got stuck in the rim. The decision was clear – I wouldn’t fix it. The weather was crazy, and I’d still lose the advantage of the tubeless system on the rear wheel. Those 23 spokes would just have to hold up!

After the fourth night, the third critical situation arose

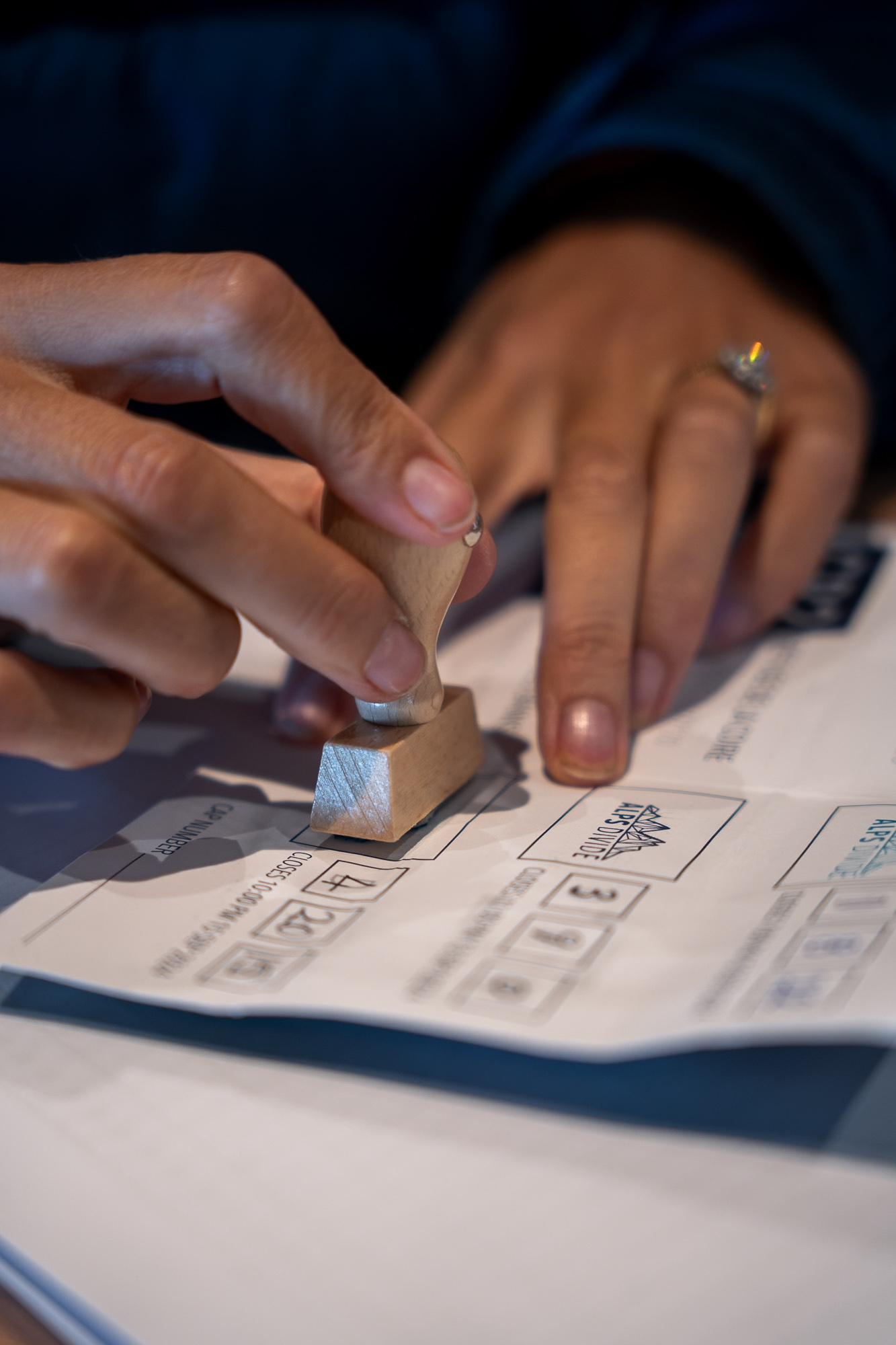

Let’s skip ahead in time and get to the rim, which is what this is all about. Anyone interested in everything that happened before, during, between, and after these segments will have to wait for the release of my book. When I left the second checkpoint in the morning, I was the last of the “favorites” (I apologize to the others, I hope I don’t offend anyone – I just can’t think of a better term). Ahead of me was a bunch of kilometers and beside me at checkpoint II was photographer Tom Gibbs from the organizing team. Only with his presence did it dawn on me that the two broken spokes, which had been throwing me off balance on descents like on a restless donkey, were actually trivial. Next to the shattered rim wall, which was right next to one of the missing spokes, this broken spoke seemed like just a cosmetic flaw. I hadn’t noticed it earlier because the rim was covered in mud, but now I was sure it had something to do with my fall in the storm at Col de la Bonette. After consulting with my fans on WhatsApp and thanks to advice from Dan Boubín from Bikelive and Alda Linhart from Kolomotion, I loosened the entire wheel to relieve the rim.

I smoked the wheel and added more necessary protections, which turned out to be very effective.

The agreement with the rim

I set off from the first position, but fear wouldn’t leave me – I kept turning around, stopping, and checking if the rim had burst. Fear is the best accelerator of problems, so I couldn’t keep it up for long. I couldn’t find any service or rental shop where I could at least borrow a rear wheel. And even if something existed, it would be far off the route and would mean a terrible waste of time. I had only one option left – to make a deal with the broken rim. In my head, a concept of its survival and purpose was forming. Somewhere near Chamoneux, where I couldn’t even see Mont Blanc because of the constant bad weather, I stopped and made the following deal with my Merit brand rim, model Turbo: “Hey, if you hold up until the end, I promise I won’t throw you away. The very next day after I finish, I’ll take you off the bike, cut you in half, and make a sculpture out of you. I’ll mount you on a wooden base, burn it, and sign it. You’ll become a traveling trophy, which winners will sign.”

I gave the rim my trust, and it gave me its – and the result was a victory in the first year of the Alps Divide!

How many similar critical situations have I experienced? How long did I then spend making that sculpture with nonfunctional hands and limited tools in our camper van? There’s no room for that in this story anymore, but maybe the photo gallery will show you.

Did you find the article helpful? Would you like to support me for my effort?

Thank you to the media team for the provided photos (please note that all photos are under the photographers’ license and cannot be further distributed without their consent).

Gavin Kaps @ospreyimagery

Tom Gibbs @bicycle_factory